While in the first post, we covered the principal old churches of Nessebar and their plans, i.e. transition from basilica to cruciform plan, and in the second post, we explored the unique decorations (or are they really unique?) of some of the 13th and 14th century churches, this post focuses more on one of the oldest churches in Nessebar.

The Church of Saint Stephen (#BYZ37) is one of the oldest churches in Nessebar, having been built sometimes during 10th-11th century. Unlike the other cruciform churches in Nessebar built in the same millenium, the Church of Saint Stephen still features a basilica plan with three naves. There were two later additions to the church. At the end of the 16th century, the nave area was extended to the west, without preserving the 3-nave plan from the previous stage. This is also the time when most of the paintings in the church were made. In the 18th century, a narthex is added to the structure, also beautifully painted. We will slowly discover all these treasures and more.

On the outside, the Church of Saint Stephen looks massive, elongated, showing big proportions. The main body of the nave is higher with a two-sloped roof. Then the other two naves have lower roofs which segment the height of the building. There are three apses on the east side, with the central one being more proeminent. Lastly, the longitudinal axis of the roof ends on both sides with beautiful walls raised above the roof, with the eastern one being slightly three-lobed. One should notice the beautiful wooden door that leads to the church yard, placed on the corner of a cobblestone street wall.

Taking a closer look at the east side facade, one starts noticing the beautiful cornice with the omnipresent sawtooth pattern that we see around the other churches, but also in the churches built by Slavic schools in the next few centuries. Below the sawtooth line, almost imperceptible, on both the central nave and the central apse cornice, a row of ceramic rosettes can be seen, with most of them unfortunately missing. So the churches built in the 13-14th century which make use extensively of this type of decoration drew their source of inspiration from this church and scaled it up by making the decorations more diverse (multiple shapes), at the same time increasing the number, the size and the importance of these specific decorations. Then blind protruted arcades hang, supported by stone corbels. Lowering the eyes, rest of the building is plain, without much decorations or even a clear building style, with tall, narrow openings. The three semicircular windows signifying the Holy Trinity stand on the eastern nave wall. The blind arcades below ”the Holy Trinity” symbols can thus represent the Christians and their faith, free from the ground, aspiring to the sky and heaven.

As said before, the plan is elongated, but there is absolutely no feeling of monotony, thanks to the raised central nave and the openings on the longitudinal wall. The brick structure is much more clear showing clearly the massive limestone bricks alternating (though not in a systematic manner) with red brick lines.

View from the southern wall. Left – the cobblestone street wall can be seen. Right – the south side with the old entrance to the church.

The interior is the most spectacular one, especially for an ecclesiastical art lover. The naos is divided in the threeaisles by rectangular columns describing an arcade at the west side, but in the front, two beautiful marble columns stand in front of the altar. As a curiosity, the columns have reversed capitals as a base, rich with deeply carved acanthus leaves. It is not clear to me whether these marble blocks or columns were crafted especially for this building or brought from another site that was dismantled.

There are two columns in front of the altar, with reversed capital as a base.

As we near the altar, we cannot ignore the beautiful iconostasis, painted in wood that embellishes the altar. The paintings date back from the 16th century, when Nessebar was obviously under Ottoman occupation. There is the same influence that we saw from the St. Paraskeva’s church, hinting to Tokap style or Mughal calico. The pattern is a rhythmic, rounded vegetable pattern, with flowers, tulips among them, hinting to the Tulip Era of the later 18th century during the reign of Ahmed III (1703-1730), when architecture and particularly the decorations blossomed ”in preparation” for the later Ottoman Baroque. A special note on the twisted rope motif which calls to an omnipresent symbol in the Balkans, a symbol of unity in faith and religion, which later can be transposed in a unity of the people.

The wooden painted iconostasis of Church St. Stephen. 1 – Two icons, one showing Jesus Christ on the throne and the other holding the head of John Baptist. The wooden beam above the icons is decorated with vegetable motifs, as well as the iconostasis below the icons. Simple wooden columns separating the icons, with plain capital and base. Twisted rope separating the icons from the above beam. 2 – close-up on the wooden iconostasis. 3 – the entrance to altar, highly decorated and a close-up of the twisted rope wood carving. 4 – An example of an 18th century calico robe (banyan) tailored in England or Holland, showing a common source of inspiration – Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, acc. no. T.215-1992.

Similar to the previous Islamic art patterns, there are colored motifs on the walls, from the same 16th century period. These are different from the Islamic art you would typically find in the Ottoman mosques and are closer to the original Persian or Indian pieces of clothing.

1 – An ogival niche, showing the icon of Jesus Christ. Below the icon there are manual (almost naive) quatrefoil representations of vegetable forms, with a flower in center. 2 – 16th century icons with sequences in the life of Jesus Christ. Below the icons there is a second type of quatrefoil colored motifs. 3 – an example of a central pattern from an 18c Indian rug showing the similar mix of colors and roughly, the same contours.

In the middle of the central nave, we can find two 18c wooden elements quite important for an Eastern Europe Orthodox church. On the right side, the Bishop throne (Episcopal amvon) proudly uncovers its detailed wooden carving. There are vegetable patterns, but also mythical creatures, as a griffin, a dragon / basilisk and a peacock, showing the abundence and the wisdom. The throne is supported by two wooden lions lying on the floor. Symmetrically placed on the left side of the nave stands the pulpit or amvon, used for special ceremonies where the priest needed to be seen and heard by a larger mass of people. This also exhibits wooden icons, framed with rich vegetable patterns (flowers and leaves).

The Bishop throne and the pulpit, both beautifully carved in wood, originating from 18c. Left – The Bishop throne in its entirety, showing the wooden lions on which the throne is supported. Middle – Close-up of the Bishop throne. Vegetable and zoomorphic symbols (griffins, peacocks, dragons). Right – the richly ornated pulpit/amvon with stairs.

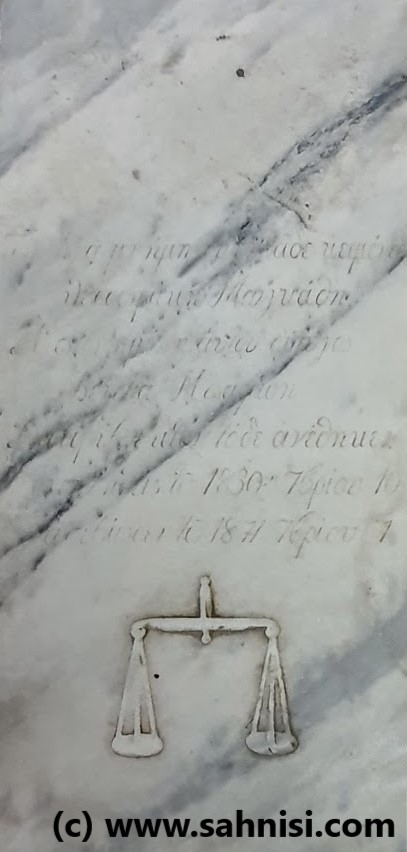

Also noticeable are the marble floor tiles. There is a marble grave slab of a Greek local as well as two other marble tiles showing the Byzantine coat of arms, also used for graves. These derive from the 19th century.

Left – Marble grave slab of a Greek local (1830-1871). Right – The Byzantine coat of arms exhibited on two other marble tiles used for graves.

The nadpis inscription from the 16th century attests the reconstruction and painting of the church. It is typical for the Eastern Orthodox churches.

The 18th century narthex deserves a special attention. First of all, the Bulgarian name is ”pritvor”, which literally means ”before the door”1. This is the narthex of the church which is a typical addition to the naos. There is another wooden throne in the pritvor, beautifully carved. The place holds much importance to the Christians as this is a preparation room before the entrance to the sacred place.

The pritvor of the church (waiting area). Left – overview of the pritvor. Right – wooden throne, embellished with lillies and tulips.

Notes

- There is a clear discrepancy between the term ”pritvor” and the similar Romanian ”pridvor”, which borrowed the term from the Slavic language, but used it differently. The narthex in Romanian churches is called a ”pre-naos / pronaos” (and not pritvor), while the pridvor is an open area before the church entrance.

Bibliography